16670

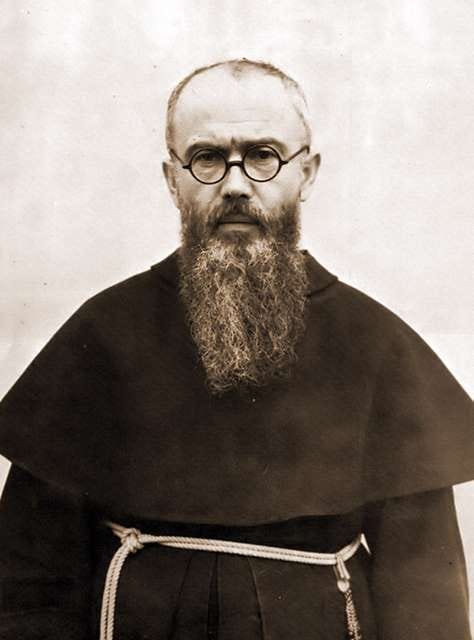

Prisoner 16670. To the men that condemned him, he was but a number, not even considered human. Yet it was this number that stood tall and firm in the face of the evil of Auschwitz. No matter what they took from him, he never let go of the one thing they truly wanted to crush: love. For his great compassion and bravery, he was awarded a seat in Heaven. Unlike his tormentors who took his name from him, he is still remembered, not as a number, but as a name, as a man, as a Saint. To them, he was Prisoner 16670; to us, he is St. Maximilian Kolbe.

St. Maximilian is commonly referred to as the Saint or Martyr of Auschwitz, and most people know of the great sacrifice involved in his martyrdom. However, it was not only that single moment that made Maximilian a Saint. Do not be mistaken, I will still discuss St. Maximilian’s final moments in detail, but first, I would like to focus on his life and what it was that made him into the man who sacrificed his life for another. He was a man who was deeply devoted to the Blessed Mother, the Immaculata, as he called Her; he was obedient to God and his religious superiors; he worked tirelessly to spread the message of Christ and the Immaculata, and he did it all with unending love and without complaints.

Maximilian and the Immaculata

If St. Maximilian was sitting beside me today, I am sure he would hate that I am writing about him and not the Immaculata. Although this is not the essay in which I shall write about the Blessed Mother, out of respect for Maximilian Kolbe, I will begin with his devotion to Her.

Maximilian’s devotion to Mary began before he was given the name Maximilian by the Franciscans, when he was still Rajmund (Raymond) Kolbe. Young Rajmund’s mother raised him on daily devotions to the Blessed Mother, including the Holy Rosary, the Angelus, and the Litany to Mary. When he was twelve, after a bout of mischievous behavior, his mother asked him, “What will become of you?” Saddened by the pain he had caused his mother, he prayed to Mary with the same question, “What will become of me?” He then had a vision in which Mary presented him with two crowns, asking which one he would accept. One crown was white, representing purity and faith, the other crown was red, representing martyrdom. Rajmund said he would accept both. From that point on, Maximilian remained deeply devoted to the Blessed Mother.

During his early years in the Franciscan friary, Maximilian felt an urge to fight for his homeland of Poland and reunify it under the patronage of Our Lady. He very nearly left the Order to join the resistance, but he was convinced by his mother to remain a friar. It was then that Maximilian realized how he was actually meant to be a soldier. With permission from his Superior, Maximilian formed the Militia Immaculatae (M.I.), an organization dedicated to spreading the message of sanctification through devotion to Mary. The M.I. slowly grew to the point that Maximilian decided some kind of publication was needed to inform members and spread the message of the M.I. even further, and so, once again with permission from his Superior, and after begging— like a street beggar —for enough money to buy a printing press, he established the Knight of the Immaculata, a free monthly informational dedicated to topics of spirituality and Catholic news. Maximilian invited his readers to join the ranks of the M.I., and soon the friary in which he lived became overcrowded with enthusiastic young men, so Maximilian took the next logical step: to build a veritable city dedicated to Mary. A Polish prince donated a plot of land to the friary, and Maximilian and his “Knights of Mary” got to work building the city. By 1937, the City of the Immaculata, or Niepokalanów, was the largest friary in the world, housing over seven hundred men.

When the Nazis invaded Poland in September 1939, they saw Maximilian Kolbe as a threat because he regularly criticized the Nazi Party in his writings, so they arrested him. While imprisoned, Maximilian provided spiritual services for his fellow inmates, and even shared his meager rations with others. He was released in December and allowed to return to Niepokalanów. As expected of a Saint, the intimidation of the Nazis failed to discourage him, and he obtained permission from the occupation authorities to continue printing, although he was severely limited in what he could write. St. Maximilian also turned Niepokalanów into a sanctuary for Jews, political refugees, and displaced families. On February 17, 1941, just after Maximilian had finished his final and most comprehensive treatise on the Immaculata1, the Nazis arrested him again.

The Suffering of Maximilian

Briefly, I would like to interject and discuss something that truly highlights St. Maximilian’s selflessness and love for the Lord. When he was in his twenties, Maximilian contracted tuberculosis. The illness caused him a great deal of suffering, and he regularly coughed up blood. On several occasions, he was ordered by his Superior to take time to rest and recuperate. The tuberculosis developed to the point that Maximilian had only one working lung, which itself was in poor condition. Despite all of this, he still dedicated his life to spreading the message of Christ and the Immaculata, working many long hours to operate the old printing press he used, helping to build a city, and even leading a mission to Japan2. He never complained about his circumstances, in fact, he maintained a more joyful disposition than most people that are perfectly healthy. The suffering he bore was only an inconvenience with the help of God and the Blessed Mother, and he continuously spread a message of love for Both to anyone he met, no matter what circumstances he was in.

The Martyr of Auschwitz

Maximilian Kolbe was sent to Auschwitz in late May of 1941. He once again shared his insufficient rations with other prisoners, and he offered to hear confessions and pray with them. He continuously prayed for the guards who beat and abused him, and he encouraged others to do the same. One day, a capo3 nearly beat Maximilian to death and left him in a ditch to die. Because of the love Maximilian had shown the other prisoners, they secretly carried him to the infirmary, where he was able to heal. During this time, he was also diagnosed with pneumonia, which, along with his tuberculosis, he would carry with him until his death. Although he was suffering greatly, Maximilian offered counsel to the other infirmed prisoners. He encouraged others to embrace their suffering as a form of sanctification.

“Everything comes to an end; this suffering, too, will end. The road to glory is the road of the cross, the royal road.” (Kluz, 195)4

Not long after St. Maximilian was released from the infirmary, the announcement came that a prisoner from his block had escaped. The Kommandant of Auschwitz had a rule that for every escaped prisoner, ten from his block would be executed. The night after the announcement, every prisoner in the block, 14A, remained awake. They were all frightened to be in the group of ten that would die. All except one: Maximilian Kolbe. Again, he consoled his fellow inmates:

“Do not be afraid, child. Death is not so dreadful, and in heaven the Immaculata awaits us.” (Kluz, 199)

The next day, the prisoners of 14A were made to stand in the July sun for hours on end. Many prisoners fainted, only to be awakened by a violent lashing. Maximilian Kolbe, however, stood tall.

“Father Maximilian, who had been doomed to die from tuberculosis twenty-five years before, did not fall; he even stood erect. He stood as the Immaculate Mother at the foot of the Cross on which God, her Son, was suspended.” (Kluz, 200)

Rapportfuehrer5 Fritsch approached the exhausted prisoners and announced that ten of them would be executed by means of starvation for the escape of their block mate. He began to walk the rows of prisoners, occasionally pointing one out for selection. One of these selected inmates, Prisoner 5659, Franciszek Gajowniczek began to cry loudly, “My poor wife! My poor children,” begging for mercy. It was then that something entirely unexpected happened: a frail, middle-aged man stepped forward.

“What is the meaning of this?” asked Fritsch.

“I want to take the place of one of the prisoners,” the man replied.

The German officer could not believe what he heard. One of the goals of the camp was to put enmity between the prisoners. How could one offer his life for another?

“Why?” Fritsch asked.

“I am a Catholic priest. This man has a wife and children; I do not,” Father Maximilian told him. Fristch decided to allow it.

The ten prisoners were led to block 13, the starvation bunker. They were stripped of their clothes and locked in the cell. No complaints or cries of anguish were heard from the bunker. Instead, Maximilian led them in prayers and hymns. The prisoners were given neither food nor water. The singing grew fainter as the days passed and another prisoner either fainted or died. Miraculously, Maximilian and four others survived for fourteen days. When the guards came into the cell to finish off the remaining prisoners, Maximilian was the only one conscious. He smiled at the guard and offered up his arm to receive the fatal injection of carbonic acid. On August 14, 1941, the eve of the Feast of the Assumption, St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe received his eternal reward. According to the orderly that collected the bodies, Maximilian’s was “strangely clean and radiant, not grimy and contorted as the others were” (Kluz, 204).

Conquering Evil

St. Maximilian’s life can be said to center around one thing: love. He loved God above all, he loved the Immaculata above all things of this world, he loved the Catholic Church and all her people, he loved the souls who had not accepted God and the Immaculata, and he loved his enemies. Everything he did, he did with love. He spread God’s love everywhere he went, even to the darkest place in the world where love was not allowed to exist.

In Auschwitz, Maximilian did a great thing, he saved a life, but he also conquered evil. He showed the prisoners of Auschwitz a light that no one else could, and he showed the Nazis that, as St. Paul wrote, “love never fails” (1 Cor 13:8). Although he was stripped of his possessions, his clothes, even his dignity, St. Maximilian never let himself be stripped of love. That is the greatest victory man can achieve against evil, and that is the marker of a true Man.

“So faith, hope, love remain, these three; but the greatest of these is love.”

1 Corinthians 13:13

You can read excerpts of this treatise with analysis here: https://saintmaximiliankolbe.com/who-are-you-o-immaculate-conception/

St. Maximilian established another City of the Immaculata, called Mugenzai no Sono, outside Nagasaki. Contrary to the urgings of everyone around him, Maximilian had the mission built on the side of a mountain opposite from Nagasaki, which, although made it harder to perform missionary work, ultimately saved the mission from being damaged by the nuclear bomb.

A prisoner criminal that was put in charge of other prisoners because of their cruelty.

Most of my information about St. Maximilian comes from Ladislaus Kluz’s book, Kolbe and the Kommandant, which you can buy here if you wish to read it: https://marytown-press-gift-store.myshopify.com/products/kolbe-and-the-kommandant

A position within the SS. Typically, their main duty was performing roll call at the concentration camps.